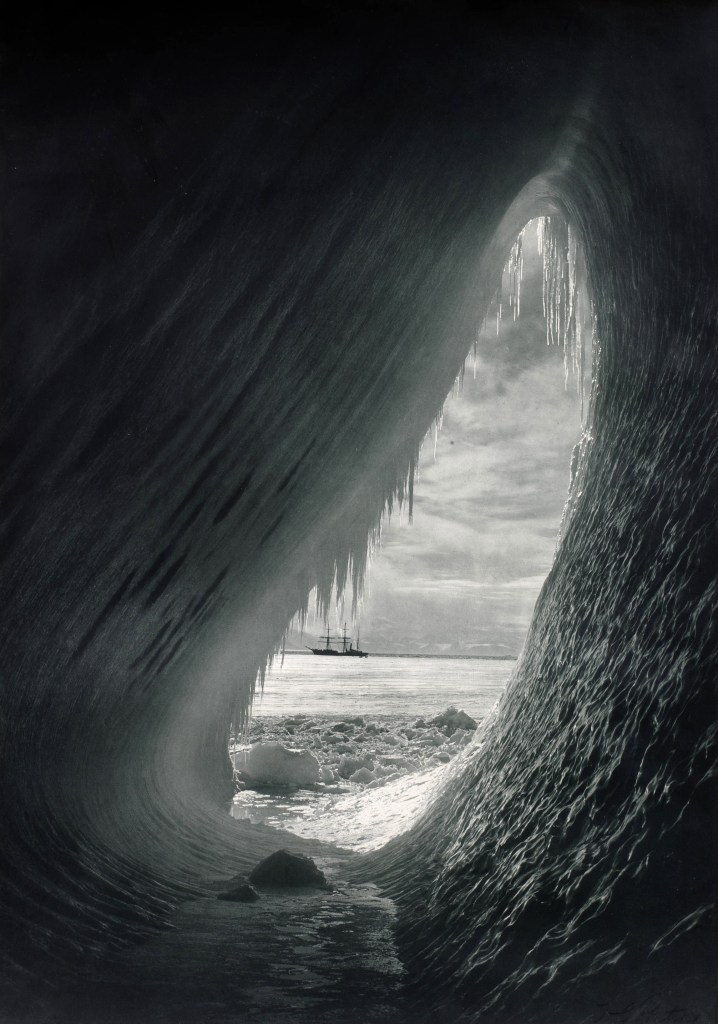

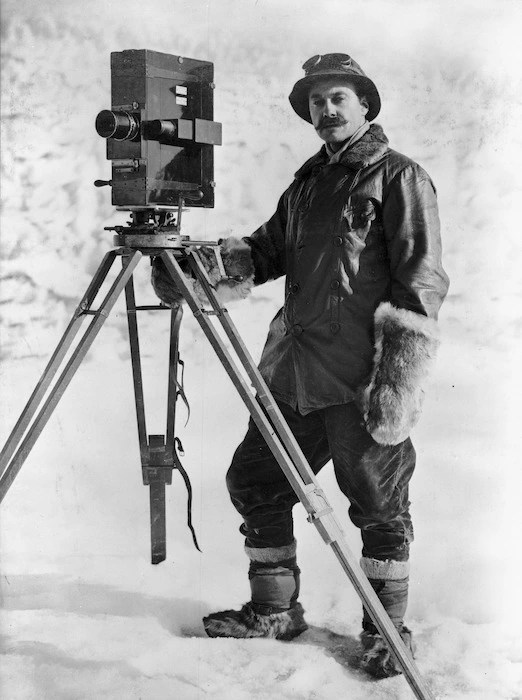

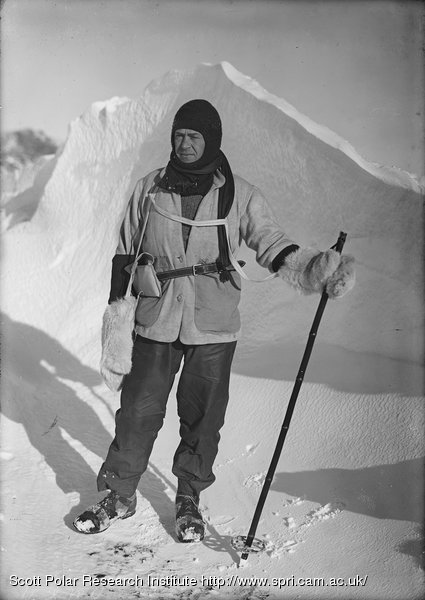

My schedule has become highly variable due to grad school and freelance work. I’m currently working on a series of posts about scientific photography on the British Antarctic Expedition–so far you can read a short introduction, and a post about Herbert Ponting’s early photographs of animals and ice. I’m still working on the next post in that series, which will focus more on the scientists of the Terra Nova expedition and their work, as seen through Ponting’s lens. Until then, here’s a new History Highlights–a periodic collection of new work and other interesting things in the history of science, exploration, and technology.

Recent History

News and new work in science, exploration, and technology.

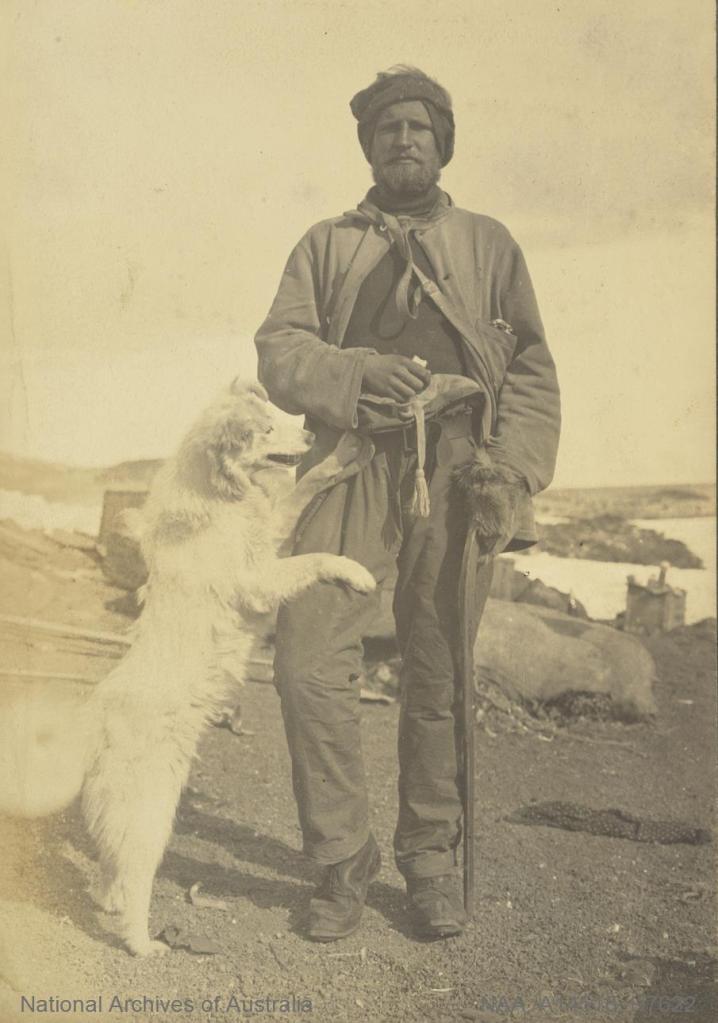

Newly Digitized Antarctic Photography

Speaking of photography in Antarctica, the National Archives of Australia recently uploaded a number of photographs from Antarctic expeditions to their online system. Their records are a little difficult to navigate, but here’s a link to the site. I’m planning to look through these images for my research, and to see if there’s anything useful for the Herbert Ponting series I’m working on.

Reconceptualizing the History of Science

Eric Moses Gurevitch shares an excellent article he wrote covering books by James Poskett and Pamela H. Smith. These works are part of an effort to broaden the history of science beyond the conventional narratives that have roots in nineteenth century chauvinisms. This re-conceptualization opens up new research possibilities in the history of science, and draws attention to the myriad ways humans have produced and shared knowledge about nature.

Miscellanea

Various highlights from my research, readings, and internet rabbit holes

Mr. Darwin’s Wild Ride

While Charles Darwin was in the Galapagos studying the rocks, plants, and animals, he used a wide variety of observational techniques. One of these apparently involved riding the tortoises:

I was always amused, when overtaking one of these great monsters as it was quietly pacing along, to see how suddenly, the instant I passed, it would draw in its head and legs, and uttering a deep hiss fall to the ground with a heavy sound, as if struck dead. I frequently got on their backs, and then, upon giving a few raps on the hinder part of the shell, they would rise up and walk away; but I found it very difficult to keep my balance.

Charles Darwin, Voyage of the Beagle

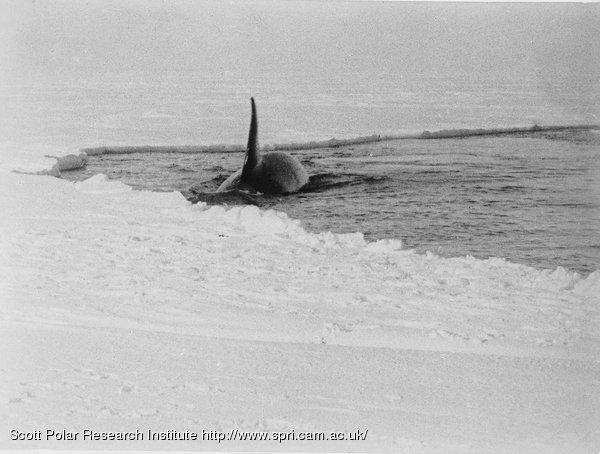

Sunken Treasure at the Bottom of McMurdo Sound

There is apparently a small treasure waiting to be recovered from the sea floor near Antarctica. As he was trying to photograph orcas from the deck of the Terra Nova, Herbert Ponting lost his favorite camera lens:

I leant over the poop rail…waiting for the whales to draw nearer, when, as I was about to release the shutter, the view disappeared from the finder, and light flooded the camera; at the same moment I heard something splash in the water. On examining the camera, what was my consternation to find that the lens-board had dropped into the sea, carrying with the the finest lens of my collection–a nine-inch Zeiss double protar, worth about £25, which had been presented to me some years ago by the Bausch and Lomb Optical Company of Rochester, U.S.A.

Herbert Ponting, The great white South; being an account of experiences with Captain Scott’s South pole expedition and of the nature life of the Antarctic

He sent a letter to Bausch and Lomb, and they sent him a new lens. But the old lens must still be there, two hundred fathoms (as Ponting claimed) under the surface of McMurdo Sound. I tried to find the lens he used, and came across a catalog from 1904 with a listing of Bausch and Lomb lenses. From Ponting’s description of the lens and his uses for it–both whales and scenic views–I think the lens below is probably the closest. I would love it if anyone with more expertise in historical photographic equipment would be able to provide some more insight.

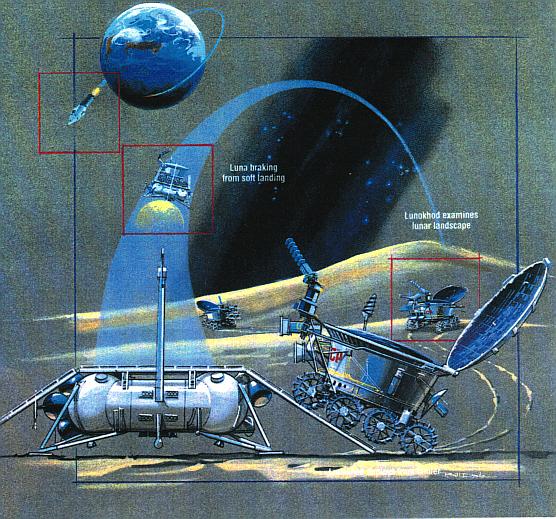

First Lunar Rover found through “Space Archaeology”

Lunokhod was a Soviet spacecraft that became the first rover on another planetary body in 1970. The rover’s solar cells deployed using a unique clamshell design, and used cameras on each side of the vehicle for navigation.

In 2010, Lunokhod 1 was found, and was even capable of being used again for scientific experiments. The rover was equipped with retroreflectors like the one left by Apollo astronauts. This is actually how its final resting site was accidentally identified, when astrophysicist Tom Murphy was using a pulsed laser to study the lunar surface. The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter was able to use those coordinates to take new images of the Lunokhod landing site and lander forty years after its original mission.

Discourse on Things that Float

Galileo apparently got into a debate with a contemporary over dinner about why things float in water. This turned into an entire treatise on how things float, in which Galileo drew from preceding work by Archimedes. He also talks about some of his astronomical work. Here are a few quotes, with an example of the type of principles he discusses in the treatise:

This sufficeth me, for my present occasion, to have, by the above declared Examples, discovered and demonstrated, without extending such matters farther, and, as I might have done, into a long Treatise: yea, but that there was a necessity of resolving the above proposed doubt, I should have contented my self with that only, which is demonstrated by Archimedes, in his first Book De Insidentibus humido: where in generall termes he infers and confirms the same Of Natation (a) Lib. 1, Prop. 4. (b) Id. Lib. 1. Prop. 3. (c) Id. Lib. 1. Prop. 3. Conclusions, namely, that Solids (a) less grave than water, swim or float upon it, the (b) more grave go to the Bottom, and the (c) equally grave rest indifferently in all places, yea, though they should be wholly under water.

But, because that this Doctrine of Archimedes, perused, transcribed and examined by Signor Francesco Buonamico, in his fifth Book of Motion, Chap. 29, and afterwards by him confuted, might by the Authority of so renowned, and famous a Philosopher, be rendered dubious, and suspected of falsity; I have judged it necessary to defend it, if I am able so to do, and to clear Archimedes, from those censures, with which he appeareth to be charged….

…The diversity of Figures given to this or that Solid, cannot any way be a Cause of its absolute Sinking or Swimming.

So that if a Solid being formed, for example, into a Sphericall Figure, doth sink or swim in the water, I say, that being formed into any other Figure, the same figure in the same water, shall sink or swim: nor can such its Motion by the Expansion or by other mutation of Figure, be impeded or taken away.

Galileo Galilei, Discourse on Floating Bodies

For more History Highlights from past weeks, click here. Follow the Inverting Vision Twitter account for updates on posts and other history of exploration and science content. Subscribe to get update in your inbox: