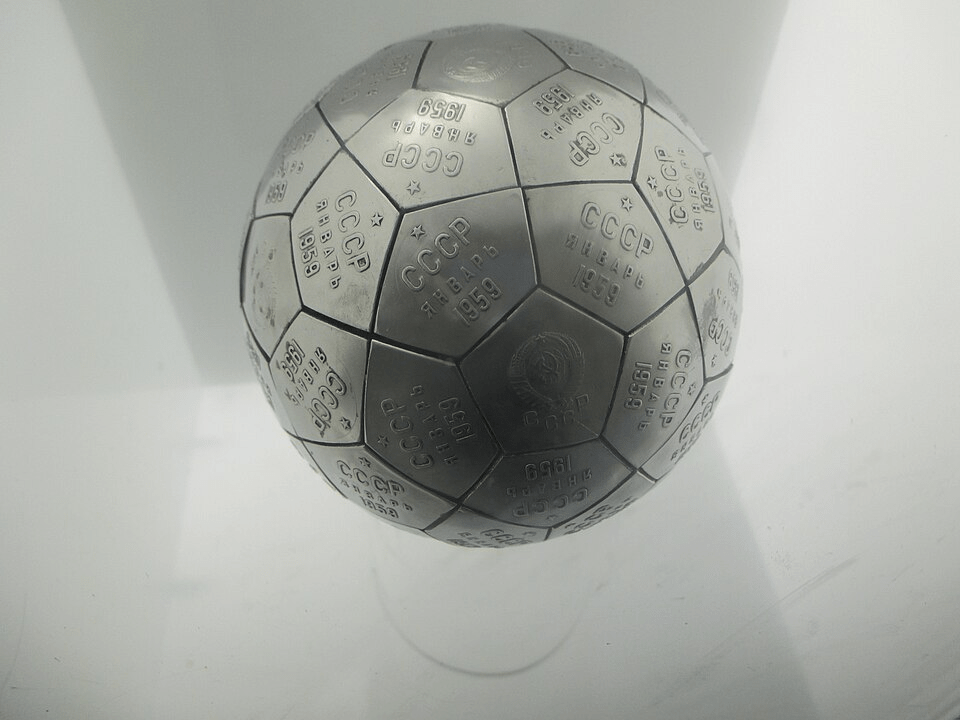

The first spacecraft from Earth to touch another world carried no people, but it did carry a unique sort of flag. Early on the morning of September 14, 1959, the Soviet space probe Luna 2 impacted the surface of the Moon. Engineers had placed stainless steel spheres aboard the spacecraft, designed to send tiny pentagonal banners across the lunar landscape. The little flags were emblazoned with the hammer and sickle, and Russian script reading: “CCCP, September, 1959.”1

The spheres were made at OKB-1, the Experimental Design Bureau where engineers worked under the leadership of Sergei Korolev to create some of the first space rockets. 2 They were commonly referred to as pennants,3 and you can find more pictures of these pennants on Don P. Mitchell’s excellent website.4 Mitchell speculates that the Luna 2 pennants probably vaporized on impact. On the other hand, the New York Times reported at the time that “[the Soviet Government] said steps had been taken to prevent the destruction of the pennants by the impact.” Regardless of their survival, the pennants accomplished an important objective.

“The day after the historic impact,” historian Asif Siddiqi writes, “[Nikita] Khrushchev triumphantly gave a replica of the ball of pendants to Eisenhower. It was a potent display of the power of politics in the emerging Soviet space programme.”5 This was the point: a spectacle designed to send a message to the United States about the Soviet lead in missile development. There was some (faint) hope on the Soviet side that this spectacle would actually end the Cold War altogether.6

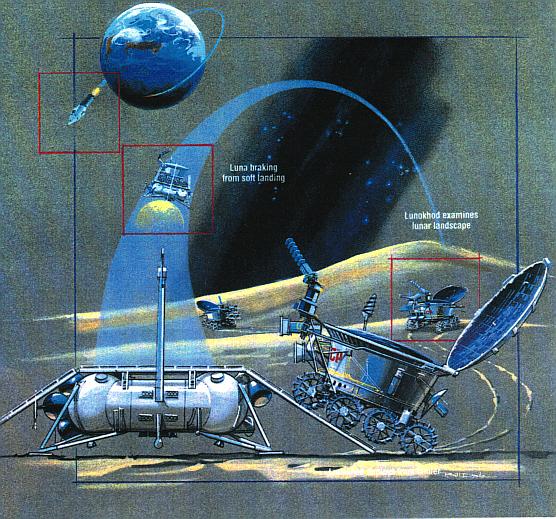

Luna 2’s pennants were just one in a series of such spectacles that constituted the Space Race. From Sputnik to Apollo, visible demonstrations of power replaced nuclear war. In the competition for geopolitical influence that was the Cold War, these projects signaled the strength of competing economic ideologies to worldwide spectators.7 In the 1950s and 1960s, this political impetus for spectacle led humans to explore the solar system up close for the first time. We sent robots to other worlds, and people to the Moon, because of a geopolitical competition. But is that the only reason we went?

I have been fascinated by the reasons people participated in the Space Race–especially the engineers and scientists who worked directly on missions to other celestial bodies. Certainly many of them were Cold Warriors, eager and willing to be recruited to a geopolitical signalling war. But not all of them were, and even those who happily went to nationalistic battle often had priorities that ranked higher in their own minds. In fact, these other motivations may have played a strong role in making the Space Race happen in the first place.

Luna 2 itself may be an example. Siddiqi explains that “contrary to conventional wisdom, it was not the Soviet Party leadership which advocated or called for Soviet pre-eminence in space at this early stage, but Korolev himself who was actualising his intense thirst to claim ‘firsts’ in the new arena of space exploration.” He goes on to say that Korolev was in partly motivated by competition with Wernher von Braun. “One wonders if there would indeed have been a programme at the time if it had not been for Korolev,” Siddiqi writes. The engineers had to convince the Cold Warriors that lunar flights were worth doing.8

Engineering ambitions and personal rivalry were not the only motivations for early space explorers. One of the most interesting examples I have seen comes from Oran Nicks, who was NASA’s director of Lunar and Planetary Programs in the early 1960s. Nicks was an engineer in a department of scientists, and that put him in a unique position. He was also not a Cold Warrior, at least not to the extent of many of his colleagues.

This isn’t to say the political pressures of the Space Race weren’t on his mind. In the early 60s, Nicks was working on the Ranger impact probes to the Moon, which were plagued by a series of early failures. In his book Far Travelers, Nicks recalls that Luna’s successes had made these failures particularly difficult. “Khrushchev had chided us publicly,” Nicks writes, “by quipping that their pennant had gotten lonesome waiting for an American companion.”

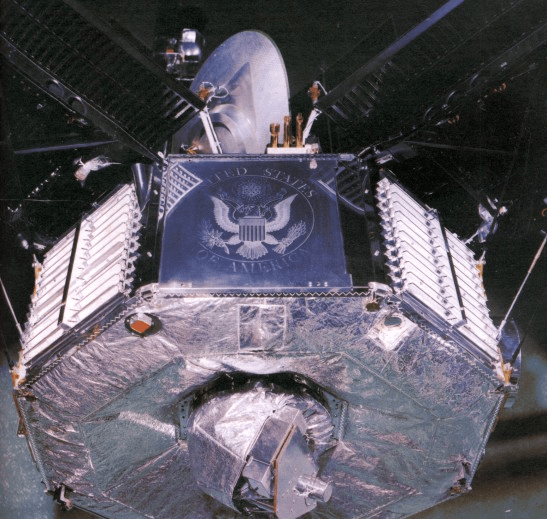

But when it came to making an overtly nationalistic response, Nicks took a different attitude. He recounts a disagreement that came up during work on a Mariner probe to Mars. Mariner project manager Jack James had suggested that the spacecraft should have the seal of the United States embossed on a panel, and went to the trouble of mocking it up.9 Nicks was vehemently opposed. Here’s what he wrote (emphasis mine):

His view was understandable; we were competing with the Russians in the race to the planets, and Americans could be proud that our “trademark” would be exhibited for current and future generations to see. My concern was that we might be accused of exhibitionism, something distasteful to me, for I was deadly serious about doing the mission for other reasons. The Russians had bragged about landing a pendant on the Moon, and I wanted no part in that disgusting game.

Oran Nicks, Far Travelers, p 37

Nicks and James compromised, and the seal made it onto the spacecraft. Nicks explains that he “insisted on a low-profile, no-publicity approach,” and was happy that “even after the successful flight there was very little publicity about the seal, and none at all negative.”10

So what were the “other reasons” that Nicks was deadly serious about? To Nicks, the American space program was a project of exploration, pure and simple. He had an expansive definition of the word “explorer” that was rooted in his view of history:

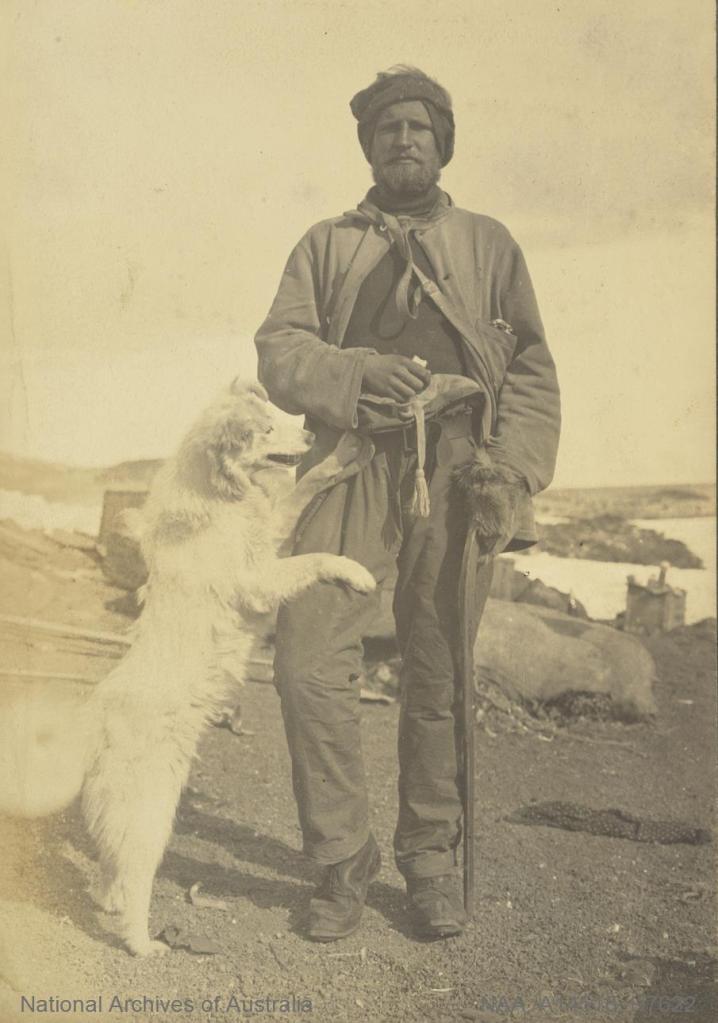

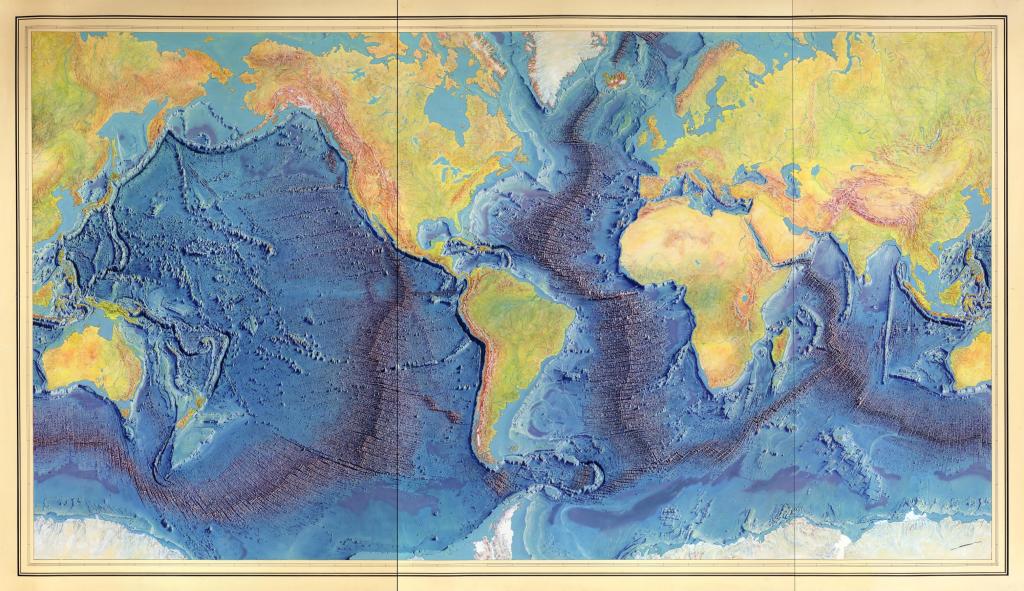

Exploration seems to be in our genes. As they developed the means to do it, men explored the perimeter of the Mediterranean, past the pillars of Hercules, to the sentinel islands off the continent…We tend now to think of exploration in a restricted sense-as a scientific, often geographic, expedition, an athletic activity pursued by specialists dressed in fur parkas like Shackleton’s or in solar topees like Livingston’s. The connotations are overly restrictive if they fail to allow for great tidal movements like the waves of people from Asia that periodically flowed west and south, or for the Scandanavians who crossed the Atlantic in numbers centuries before Columbus. These waves of venturesome people were of a higher order than the random movement of nomads seeking fresh forage…We must conclude that for some of the species, long and perilous passages were no real deterrent to the exploring imperative.

Oran Nicks, Far Travelers, pp 6-7

Nicks is conflating a series of explorations that all occurred for different reasons ranging from survival, to geopolitics, to science. To him, they are part of an innate impulse that all humans have in common. He is situating himself, the United States, and the Soviet Union in a grand tradition that encompasses all of human history.

He was not the only person to do this sort of thing. The space explorers of the 1960s often invoked historical analogy–in the US, this was often the narrative of the American frontier. But these analogies were often related to more specific impulses: colonization, adventure, competition, scientific investigation. Nicks’ framing of exploration as an “instinct” is somewhat distinct. He believes that exploration is something done for its own sake, out of sheer curiosity. The scientific investigations on the missions he managed were an expression of this curiosity, rather than a means to some other end.11

Chertok, in his reflections on the Soviet space program, also remembers people thinking beyond the geopolitics:

Cosmonautics did not arise simply from militarization, and its aims were more than purely propagandistic. During the first post-Sputnik year, the foundations were laid for truly scientific research in space, serving the interests of all humankind…I am not writing about this out of nostalgia for the ‘good old days,’ but because I remember well how people from the most diverse social strata felt about our space successes.

Chertok, Rockets and People, Volume II, pp 435-436

The space programs in both nations were collaborations between people with widely varying motivations. They convinced their governments that pursuing certain objectives in space also served the ends of the state. They competed with each other for funding and for influence over the long-term direction of their programs. In this context, geopolitical competition seems like less of a direct motivation for space exploration, and more of an enabling factor that unlocked resources for would-be explorers.

- Siddiqi, Asif A. “First to the Moon,” Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, Vol 51, pp 231-238, 1998, PDF: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5ef8124031cfcf448b11db32/t/5f1c476085d7250b810190c1/1595688803275/Siddiqi+First+to+the+Moon+1998.pdf ↩︎

- Chertok, Boris, ed. Asif Siddiqi, Rockets and People, Volume II: Creating a Rocket Industry, NASA, 2006, pp 446-448 PDF: https://www.nasa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/635963main_rocketspeoplevolume2-ebook.pdf?emrc=5bed7c ↩︎

- Are they called “pennants” or “pendants”? Contemporary newspapers, Mitchell and most other sources say pennants. Siddiqi and Chertok say pendant. Seems to come from a comparison made to ship’s pennant displays (Chertok, in unsourced quote from 447). Wikipedia says pendant is an obsolete spelling of pennant, citing the Dictionary of Vexillology. ↩︎

- I’m probably going to link to Mitchell and Sven Grahn a lot on this blog. They have both done amazing work on early Soviet robotics, among other topics, and their work has led me to important sources. You should check out their websites and their books. ↩︎

- Siddiqi, p 235-236 The image at the top of this post shows an additional replica, now sitting in the Kansas Cosmosphere. The original replica is held by the Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum. ↩︎

- Chertok, p 447 Certainly it seems like Chertok may have believed this, or believed that Soviet leaders held that hope. “Alas,” he writes, “this did not happen. It was not in our power.” ↩︎

- See MacDonald, Alexander, The Long Space Age: The Economic Origins of Space Exploration from Colonial America to the Cold War, 2017, Yale University Press. Especially Chapter 4. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1n2tvkx.8 ↩︎

- Siddiqi, pp 231-232 ↩︎

- Nicks, Oran, Far Travelers: The Exploring Machines, NASA, 1985, https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/19850024813 ↩︎

- Nicks, p 37 ↩︎

- Werner Von Braun, for example, was certainly motivated by colonization and also religious notions. Historian Catherine Newell writes about religious aspects of the American space program in her book Destined for the Stars. Historian Michael Robinson has talked about “true believers” among other types of space explorers. Russian cosmism was a big influence on early Soviet engineers. I plan to do a taxonomy of space explorers at some point, going through various motivations and the historical analogies used to justify and explain them. I see Nicks’ expansive definition of exploration as human instinct most reflected in Carl Sagan’s writings. ↩︎