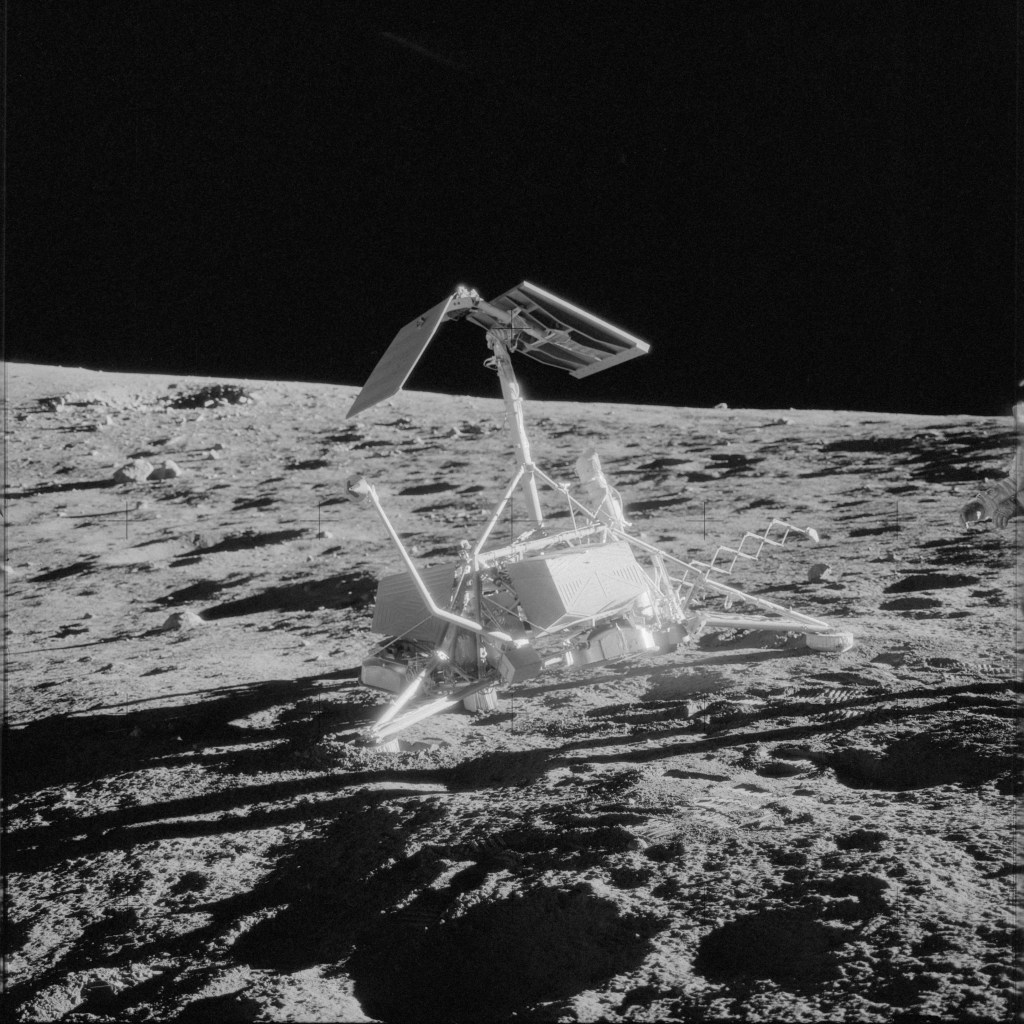

The Odysseus lunar lander built by Intuitive Machines (IM) recently became the first U.S. robot on the Moon’s surface since the Surveyor landers in the 1960s. Earlier this week, IM worked with NASA to get pictures of the lander from orbit. The resulting image is impressive, showing the lander as a tiny speck in the vast grey landscape near the Moon’s south pole. The image is also an echo of the first time NASA managed this feat, 57 years ago. In 1967, NASA’s third Lunar Orbiter spacecraft snagged a photograph of Surveyor I. The story of how engineers acquired that photograph (and it is a literal analog photograph) is fascinating, and the image itself played an important role in getting Apollo astronauts to the Moon. First, here’s the image of Odysseus along with the historic photograph of Surveyor:

It’s a bit easier to see Odysseus in the new image than it is to see Surveyor in the Lunar Orbiter (LO) photograph. But both of them are pretty difficult to spot, beyond the telltale shadow. And making out any detail is impossible. So what’s the point? For NASA in the 1960s, it was all about safety.

At the time, the push toward the Apollo landings was quickly accelerating. One of the top priorities was to find suitable landing sites. Telescopic imagery of the Moon was fairly comprehensive, but had some serious limitations, so NASA initiated the Lunar Orbiter program. Engineers put robots into orbit around the Moon, equipped with Kodak cameras and film, and took high-resolution images of potential Apollo landing sites.1 Meanwhile, they Surveyor robots soft-landed on the surface, took pictures, and used scoops to dig into the soil. Knowledge about the nature of the lunar surface grew rapidly. It began to quell doubts that some scientists held about the potential of landing people on the Moon.2 The imaging of Surveyor landing sites was an important part of this process.

For scientists in the 1960s, seeing the lander wasn’t as important as seeing the area around the it. Images from the ground could help scientists understand what they were seeing from above. At the time, orbital imagery was pretty difficult to interpret. Shadows were used to figure out the height or depth of some features, but other patterns in the orbital imagery were harder to make sense of. Scientists used aerial imagery of Earth to get started, since you could easily compare pictures of mountains and canyons taken from airplanes to the real thing.3 But the forces that shaped features on Earth weren’t necessarily the same as those that shaped features on the Moon, so the Earth-analog method was not always a reliable guide. What they really wanted were images from the lunar surface. That’s what Surveyor landers were able to provide.

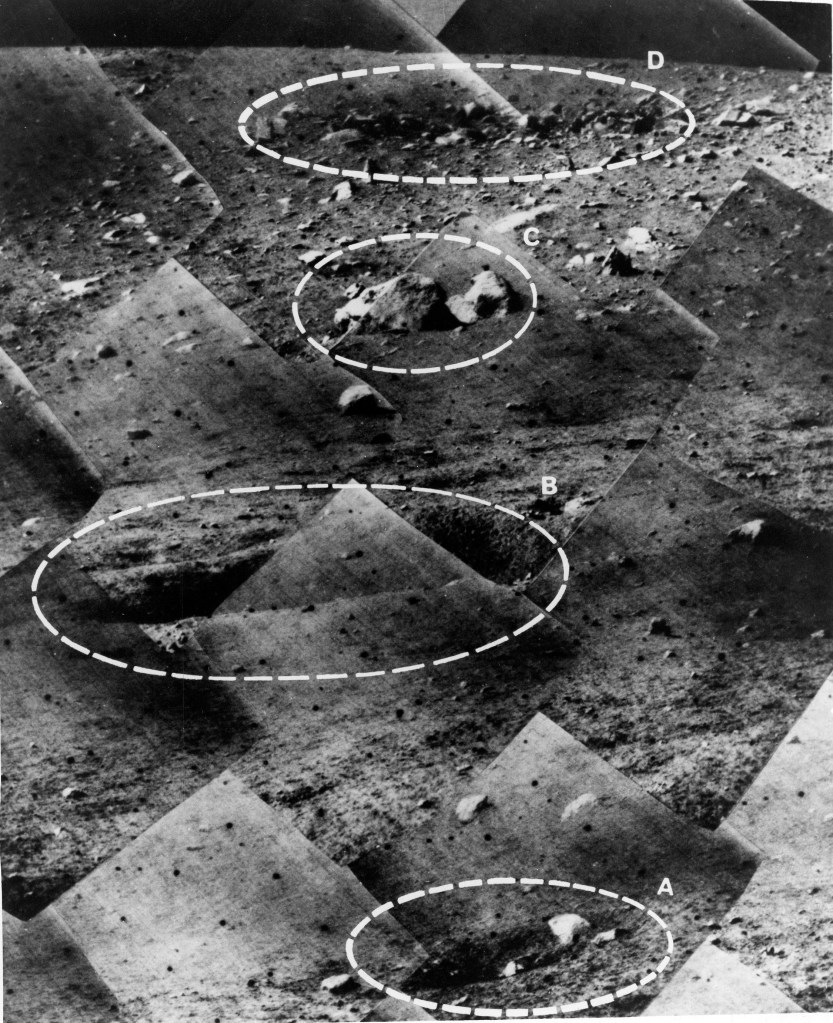

If scientists could compare orbital images with ground-based images of the real lunar surface, they could be more confident in their interpretations. This could make it easier to select Apollo landing sites with confidence. And that’s exactly what they did using a combination Surveyor and Lunar Orbiter imaging. The story of Surveyor III gives us a great example of this.

In the same mission that took the photograph of Surveyor I, engineers also took photos of the planned landing area for Surveyor III (which launched while LOIII was still in orbit around the Moon). They hoped that a successful Surveyor III mission would then provide images from the ground that scientists could compare to orbital imagery. The plan was a complete success. Using pictures from Surveyor III, they were able to isolate the exact position of Surveyor III in the orbital imagery.4

Scientists got a lot of great data from the robots. Apollo planners analyzed the images and data, and used the information to plan Apollo landing sites. They were able to find places that were both safe for landing, and scientifically interesting. For scientists, that generally meant trying to land Apollo astronauts in places that were geologically distinct.

This wasn’t really something that many of the astronauts were particularly interested in, at least at first. They were something of soldiers in the Cold War, and neither they nor the government officials directing the program thought that science was the main priority. The priority was getting a man to the Moon before the Soviet Union.5 The selection of later Apollo sites based on scientific interest was, at least in part, a concession to the scientists who were integral to the safety and success of the mission’s primary objective. But this isn’t to say that these groups saw no use for science within Apollo. Science itself could also serve Cold War goals, as it became a source of prestige–a pattern in scientific exploration going back centuries.

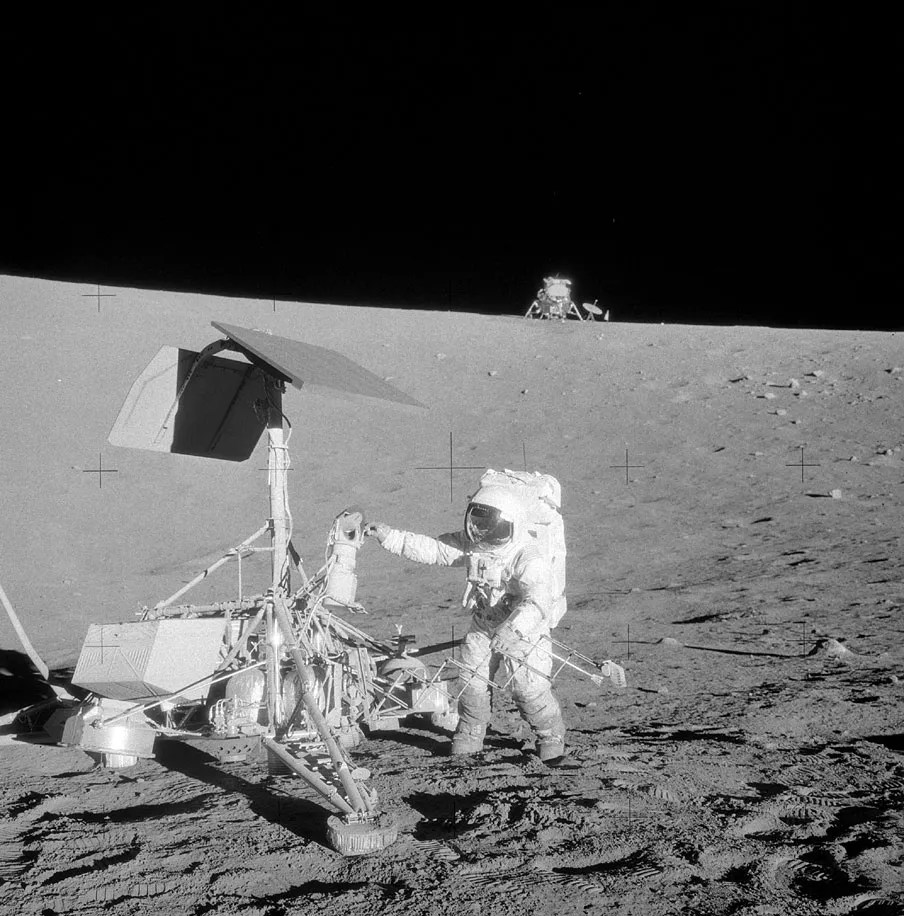

With Apollo 12, the story of Surveyor III came full circle and we got one of the coolest pictures ever taken from the lunar surface. Out of scientific and engineering interest, Apollo 12 landed in the same site as Surveyor III. Al Bean and Pete Conrad got to see the robot up close, which is how we have the image from earlier showing Surveyor sitting on the Moon. They took pictures, and even grabbed pieces of the robot to bring back home for analysis. Right now, the TV camera of Surveyor III sit in the Smithsonian, where you can visit and see actual hardware returned from the Moon. The Apollo astronauts also took what I think are some of the most incredible photographs from the history of exploration–human space explorers interacting directly with their robot counterparts.

CORRECTION 11/21/2024: The original version of this post identified the astronaut in the last picture as Alan Bean. It’s actually Pete Conrad, and Alan Bean is the one taking the photograph.

Footnotes:

- If you want to know more about this, Lunar Orbiter photography was the topic of my master’s thesis, which can be found in the about section. ↩︎

- There’s a famous story of how scientists feared the landing vehicle would sink into the soil, an idea that did come from a fairly well-known scientist. But many geologists at the time were pretty dismissive of his claims. There were other potential issues though, including ignorance of the electrostatic properties of the lunar material, which could have led to severe dust build-up on equipment. Bottom line: not a lot was known for sure about the nature of the surface. This was an issue if you wanted to land there. ↩︎

- For a description of lunar mapping efforts around this time, see Kopal and Carder, Mapping of the Moon. The difficulty of interpreting the photographs can be seen in a variety of scientific papers from the time. Examples can be found in Interpretation of Lunar Probe Data, ed. Jack Green, 1966. ↩︎

- Boeing was the primary contractor on Lunar Orbiter. Images and methods can be found in their contractor reports for NASA. ↩︎

- Detailed comments the relative priority of science on the Apollo Mission can be seen in A Review of Space Research, the document that came out of the 1962 Iowa Summer Study. ↩︎