FLIP, Laboratory at Sea

Stefan Helmreich writes about FLIP (FLoating Instrument Platform), a fascinating vessel designed for oceanographic research. First launched in 1962, it has the unique ability to change orientation, immersing most of its structure into the ocean to become a buoy. This provides a relatively stable platform for research, and the ability to do semi-controlled experiments on waves. It is an example of how the distinction between the laboratory and the field is sometimes blurred, in part due to technology.

You can read more of Helmreich’s analysis in Media+Environment and ISIS.

Looking Back on InSight and Phoenix on Mars

Mars InSIght is gathering dust on Mars, and its days are numbered. The robotic mission has been an enormous success, contributing to our understanding of Martian geology and natural history. NASA has an excellent retrospective on the major scientific achievements of the InSight lander.

Around this time of year in 2008, the last signals were received from the Phoenix lander. Like the InSight mission, Phoenix lasted beyond its mission parameters, and eventually succumbed to the elements. NASA also has a short history of the Phoenix lander.

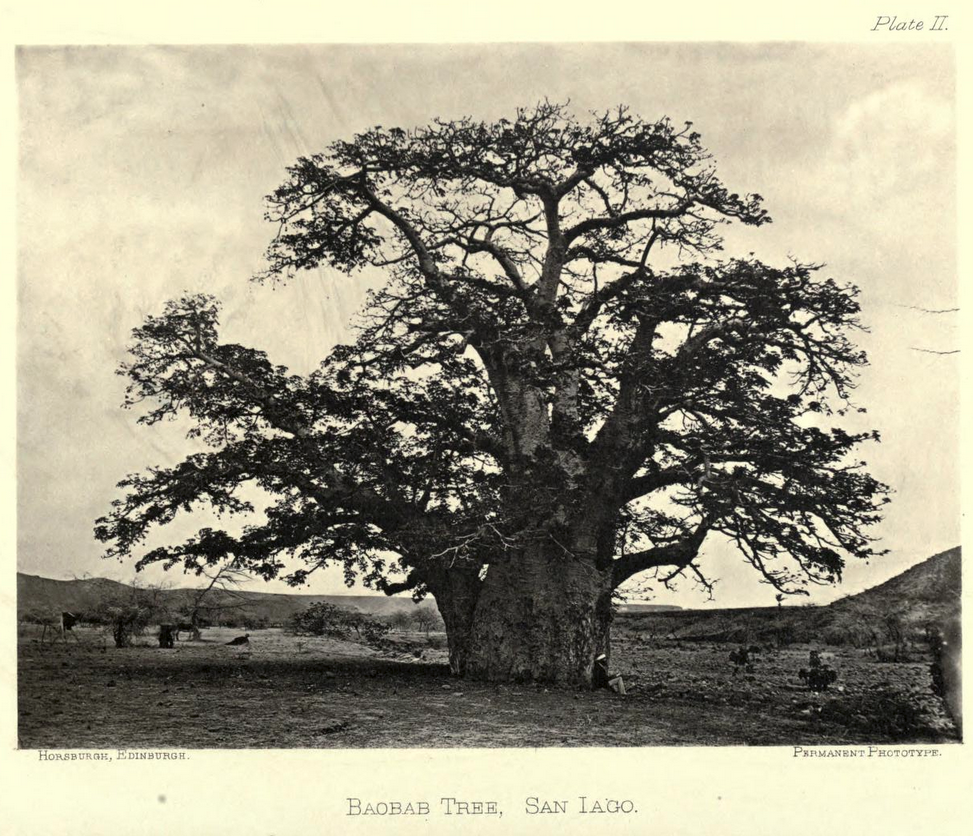

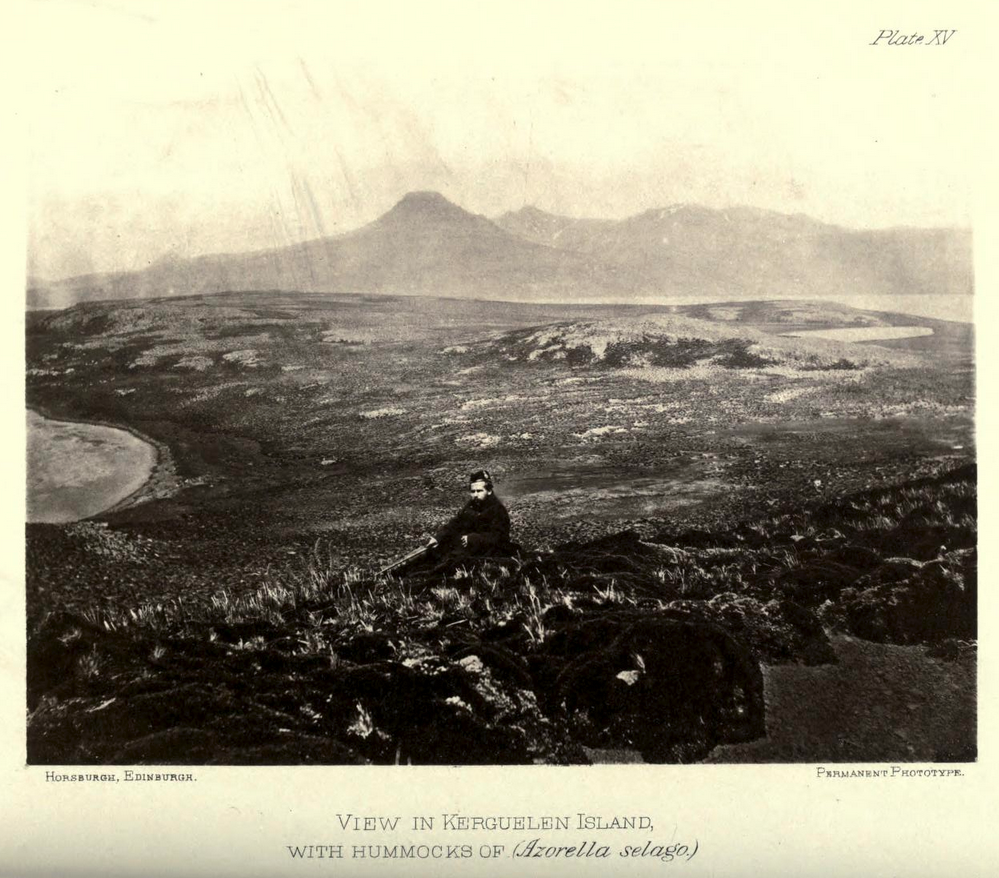

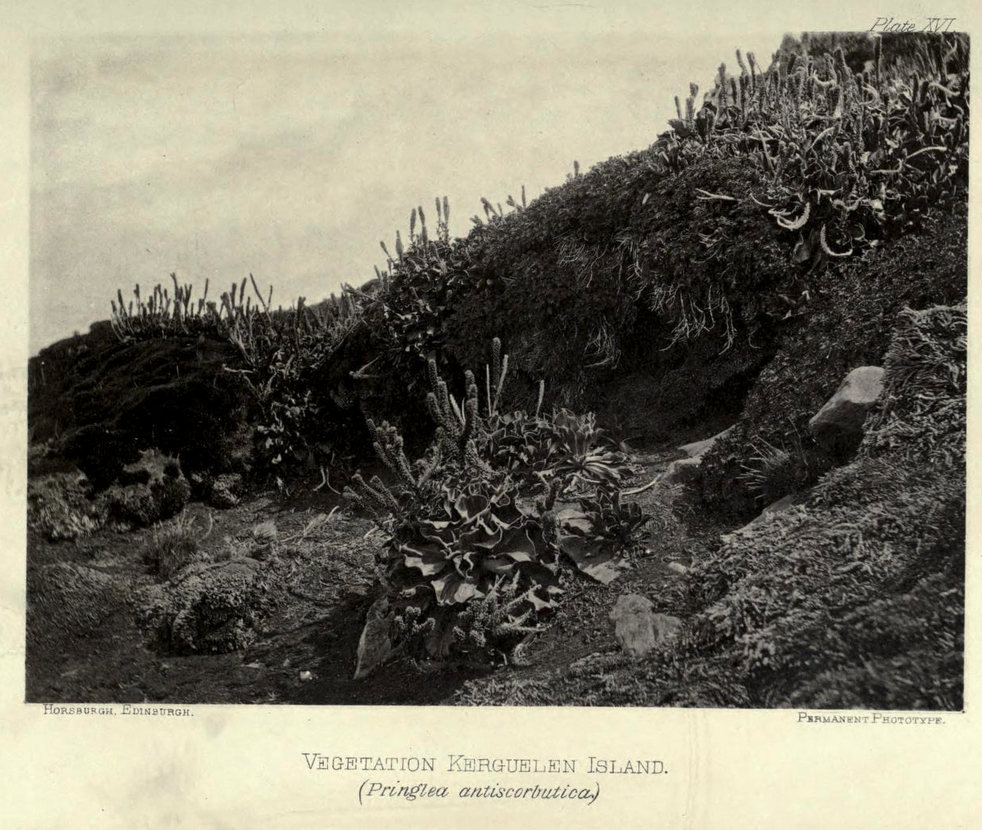

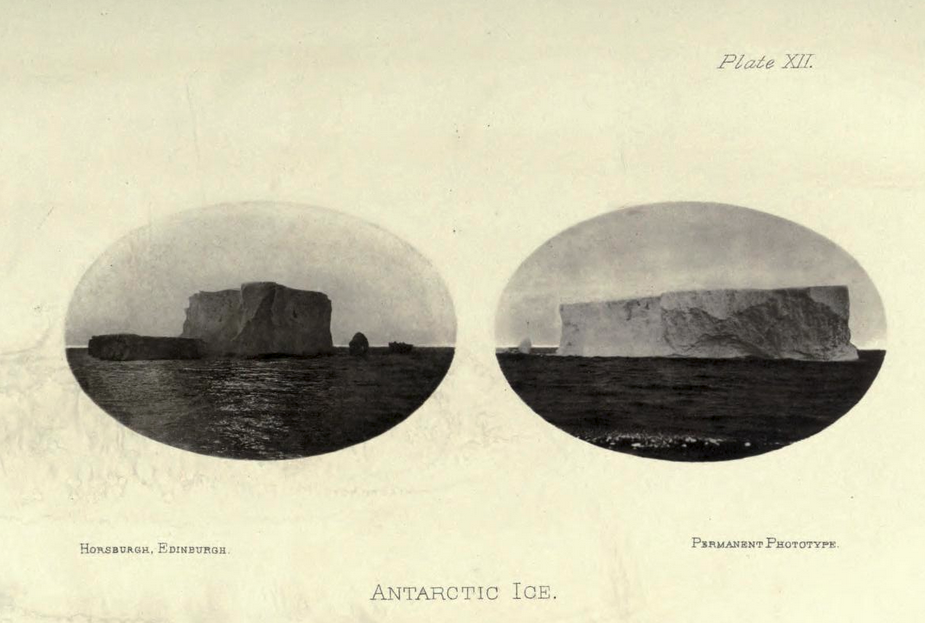

Photographs From the HMS Challenger

The HMS Challenger expedition helped kickstart the discipline of oceanography. The voyage is a monumental saga in the history of science and the history of exploration. It also played an important role in the history of photography. Not much is known about the photographers and the equipment they used. I was able to find a letter to the editor in an 1875 issue of Nature, referencing a new type of dry photographic plate. The letter was written by Henry Stuart Wortley, and seems to imply that a collodion process was used, including a combination of wet and dry plates. I want to investigate this further, but for now, here are a few of my favorite photographs from the official narrative of the expedition:

The Place of All the Demons

In the 1940s and 1950s, scholars were starting to think seriously about how to create artificial intelligence. They wrote papers and met regularly to discuss things like neural networks and machine learning. Oliver Selfridge was an important part of this conversation, and contributed to a number of early breakthroughs in thinking about artificial intelligence. One of these was a pattern recognition model that laid the foundations for computer image processing.

He imagined each node in the network as a hierarchical group of “demons” each assigned to recognize certain patterns, and to shout out when they recognize something like their assigned pattern. He wrote that each demon might “be assigned one letter of the alphabet, so that the task of the A-demon is to shout as loud of the amount of ‘A-ness’ that he sees in the image.” Then a demon at the top of the hierarchy listens to all the shouting and picks out the loudest shout as the best interpretation of the image.

He called the model “Pandemonium.”

Additional Links:

The Quest for Artificial Intelligence, by Nils J. Nilsson

“A Waste Land of Famine and Despair”: Kepler’s Tortured Personal Life

I want to do a review of The Sleepwalkers by Arthur Koestler at some point. Until then, here’s a short bit about Kepler. Kepler’s personal life was just so absurdly tragic that it stood out to me.

According to Koestler, we get this stuff from Kepler himself, who wrote an incredibly detailed family history. Koestler dwells on it at length, providing a detailed glimpse into the background and mindset of his subject. Here’s a brief outline of Kepler’s life. All quotes here are from Koestler, and I think some of them reveal his talent for colorful description.

- “Johannes Kepler’s father was a mercenary adventurer who narrowly escaped the gallows. His mother, Katherine, … was brought up by an aunt who was burnt alive as a witch, and Katherine herself, accused in old age of consorting with the Devil, had as narrow an escape from the stake as the father had from the gallows.”

- When Kepler was about three years old, his parents both left to fight Protestants in the Netherlands, despite being Protestant themselves. Kepler was left with his grandparents. His father went on two more trips, then disappeared.

- He had six siblings, “of whom three..died in childhood, and two became normal, law-abiding citizens. But Heinrich, the next in age to Johannes, was an epileptic and a victim of the psychopathic streak running through the family.”

- “Johannes was a sickly child, with thin limbs and a large, pasty face surrounded by dark curly hair. He was born with defective eyesight…his stomach and gallbladder gave constant trouble; he suffered from boils, rashes, and probably from piles, for he tells us that he could never sit still for any length of time and had to walk up and down.”

- When he was four, he contracted smallpox and nearly died.

- He compared himself to a dog constantly, even saying he had an aversion to bathing.

- “Kepler belonged to the race of bleeders, the victims of emotional haemophilia, to whom every injury means multiplied danger, and who nevertheless must go on exposing himself to stabs and slashes. But one customary feature is conspicuously absent from his writings: the soothing drug of self-pity, which makes the sufferer spiritually impotent, and prevents his suffering from bearing fruit.”

- Kepler’s first wife “resented her husband’s lowly position as a stargazer and understood nothing of his work.” He describes her in extremely bitter terms after she died at thirty-seven. Three of their five children died very young.

- He had seven children with his second wife, “of whom three died in infancy.” Koestler presumes that his relationship with her was better than with his first wife, since he doesn’t write about her very much.

- He was forced into virtual itinerancy in his last years, while trying to get some of his works printed. He spent ten months away from his family, and “was again plagued by rashes and boils; he was afraid that he would die before the printing of the Tables was finished; and the future was a waste land of famine and despair.”

- After the struggles with publishing, he had difficulty obtaining payment for his work and accessing money owed to him. “He had money-deposits in various places, but he was unable to recover even the interests due to him. When he set out on that last journey across half of war-torn Europe, he took all the cash he had with him, leaving Susanna and the children penniless.”

- He ended up in Ratisbon to try to get payment from the Emperor, but contracted a fever and died there in 1630.

And then there’s this quote from Kepler’s self-description that I quite identify with:

“In this man there are two opposite tendencies: always to regret any wasted time, and always to waste it willingly.”

Links:

The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man’s Changing Vision of the Universe, by Arthur Koestler