In the rivers of Great Britain and western Europe lives an eel that was once at the center of a great scientific mystery. The European eel was frequently caught in nets or farmed in fisheries for centuries. Cookbooks featured them in a wide variety of dishes. But the origins of the eel were a mystery since no one had observed an example of a young eel. There are records speculating about their spawning and migration patterns going all the way back to Aristotle, who claimed that they came from earthworms (Aristotle, History of Animals 6.16). The mystery wasn’t solved until the 20th century when Danish researchers put together a series of voyages that ended with a circumnavigation of the world.

Dr. Johannes Schmidt was a Danish biologist who committed much of his career to studying these eels. Historian Bo Paulsen has written an overview of Schmidt’s career, describing him as “a forerunner of Jacques Cousteau.” Schmidt was a dedicated scientist with a keen awareness of public outreach. And in the early 20th century he established a name for himself in the world of biology and marine science.

Around the time Schmidt was building his career, an international community of scientists was flourishing. This community had been cultivated through international journals and direct communication between scientists around the world, and it was infused a spirit of healthy competition through fairs and exhibitions. But the outbreak of World War I threw the international scientific community into disarray. After the war, there was a desire amongst many scientists to rekindle the collaboration and scientific activity. This included prominent Danish scientists, who sought to resume research and collaboration in the post-war years.

It was in this moment that Johannes Schmidt began working with collaborators on a project to resolve the mystery of the European eel life cycle. Schmidt was a committed nationalist, however. He kept the prestige of Denmark in mind, which may have been part of his motivation for suggesting a circumnavigation project reminiscent of the Challenger expedition fifty years earlier. And so while one of his partners suggested making the project an international endeavor through the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea, it remained primarily a Danish endeavor.

Schmidt and his partners planned their expeditions with backing from the Danish government, the East Asiatic Company, and funding from the Carlsberg Foundation. The founder of the Carlsberg Brewery, J.C. Jacobsen was a prolific patron of science. He established the Carlsberg Research Laboratory with the goal of leveraging science to produce the best beer possible. It was (and continues to be) a dedicated research facility studying chemistry and biology that might have applications to the brewing process. He also founded the Carlsberg Foundation, Denmark’s first commercial foundation, to support the development of science more generally.

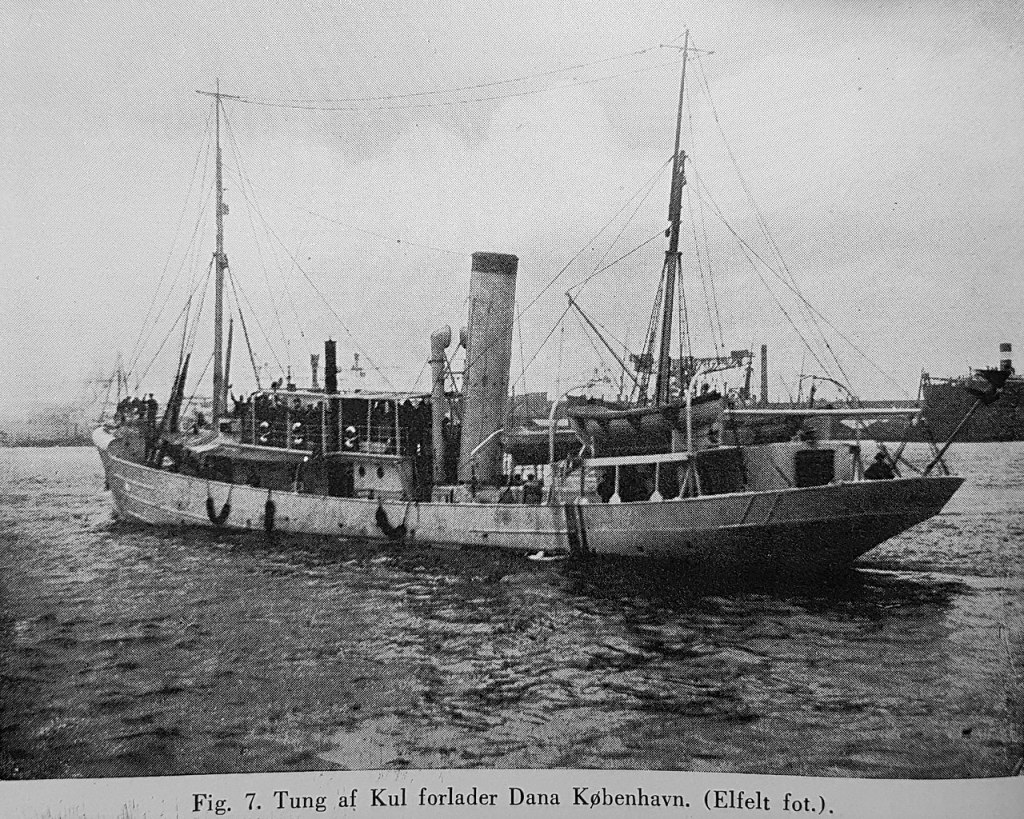

Johannes Schmidt had developed deep ties with the Carlsberg scientific network, which proved useful in funding the eel expeditions. With the support of the East Asiatic Company, Schmidt and his team were able to secure a motor schooner, the M/S Dana, equipped with an engine and four masts. The vessel was outfitted with winches and scientific instruments for collecting samples from deep ocean waters. The M/S Dana was used for the first two expeditions in the Atlantic allowing its crew to collect information about the distribution of eels. A second ship, the R/V Dana, was built for a third expedition and specifically designed for scientific research. The vessel was equipped with an electric winch driving a special phosphor-bronze wire rope 10 kilometers long, making it easier to collect samples from deep waters. To make depth measurements the ship with outfitted with echo sounding equipment, which was a relatively new technology at the time.These early Dana missions successfully recovered eel larvae and plotted their positions in the Atlantic–necessary data for solving the age-old puzzle of the European eel.

It turned out that the eels spawned deep in an area of the Atlantic Ocean known as the Sargasso Sea. This is an area of the Atlantic with strange properties that were first recorded by Christopher Columbus. The Sargasso Sea is encircled by four different ocean currents, leaving it effectively isolated from the rest of the ocean. Over time it has collected an enormous amount of seaweed (and now trash), which along with its position in the horse latitudes contributed to legends of ships disappearing in its waters. After spawning in the Sargasso, eels migrate to western Europe where they live out most of their lives.

The Dana expeditions were a massive success for Schmidt and for Denmark, and eventually led to funding for further exploration. As is often the case, the new information led to more questions. The population of eels in other parts of the world could now be studied with a greater understanding of the eel life cycle. In a 1929 summary of the expeditions in Nature, these question were laid out:

“Why are eels plentiful throughout the western Pacific, but absent from all the eastern half of that ocean? Why are they present on both sides of the North Atlantic ocean, but absent from both sides of the South Atlantic? Why are they plentiful on one side of Australia and absent from the other?”

Nature, No. 3087, Vol. 122, Dec 19 1929 “The Dana Expedition”

In 1928 Schmidt’s vision of a circumnavigation became a reality. The final scientific voyage on the R/V Dana collected more information about eel spawning behavior in the Atlantic, bolstering Schmidt’s theory about the Sargasso sea spawning patterns. The expedition traveled through the Panama Canal into the Pacific Ocean, eventually finding eel larvae near Tahiti and providing insight into Pacific spawning patterns. The crew of the Dana then charted the distribution of eel species in the Indian Ocean before returning to Europe. Along their way they took a number other oceanographic measurements, including water temperatures and other oceanic conditions. A write-up in Nature even suggested that the strange spawning patterns of European eels lent support to the theory of continental drift (referred to as “Wegener’s theory of continental shifting”).

The technology used by the Dana reflects a transitional period in the history of oceanography. The sample collection methodology they used was in principle the same as those used in the 19th centuries–nets, cables, and winches. But they were also equipped with echo-sounding machines and short-wave radios for communication. The Dana expeditions had a lasting impact through their contributions to science and their public outreach–they are one part of a rich history of Danish marine science and the broader history of modern scientific research practices.

Pingback: History Highlights 3: Mapping the Ocean, Living Museums, Ancient Arctic Visits – Inverting Vision