This is part two of a series of posts about photography and science on the Terra Nova expedition of 1910-193. You can read the introduction here. This week we find Ponting arriving in Antarctica, and beginning to get acquainted with the environment.

Scientific curiosity drew photographer Herbert Ponting to Antarctica. Before his journey with the British Antarctic Expedition in 1910, the great southern continent was already a place of growing scientific interest. Early encounters in the late 18th and early 19th centuries had revealed ice shelves, animals, and mountains that encouraged dedicated missions to chart and understand the continent. James Weddel, Jules Dumont d’Urville, Charles Wilkes, and James Clark Ross revealed the contours of Antarctica, and returned to Europe and the United States with tantalizing information for biologists and geologists.

Herbert Ponting was particularly interested in the animals of the Antarctic. Several years before Ponting climbed aboard the Terra Nova, his crew mates Robert Falcon Scott and Edward Wilson had made a landing on Ross Island during the Discovery expedition. In his diaries, Wilson vividly described the smells and sounds that greeted them when they made landfall at Cape Crozier–they had found one of the largest colonies of Adelie penguins. Ponting fantasized about being able to make camp at Cape Crozier and photograph the penguins there, but Scott chose Cape Evans on the other side of the island for their base of operations.

Once they arrived, the crew used their tracked motor sledges to unload shelter materials and supplies. Ponting still had plenty of opportunity to observe and photograph wildlife. There was a colony of Adelie penguins near their camp, and the birds were not shy about greeting the visitors. “They strolled about,” Ponting wrote, “for all the world like a party of tourists taking in the sights.”1 This delighted the photographer, and he took photographs of their interactions with the crew, who liked to play games with the penguins.

Later in the expedition, the scientific team would learn more about the life cycle and behaviors of the penguins. In the meantime, the crew at Cape Evans spent time studying other examples of marine life. The biologist Denis Lillie collected as many samples as possible with nets. These included an example of cephalodiscus, which are wormlike animals that live in colonies. They also caught “crustacea, star-fish, sea-urchins, great worms, anemones, molluscs,” and large glass sponges.

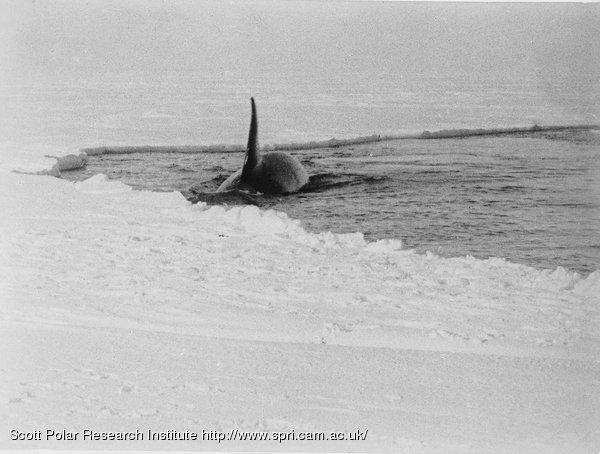

But Ponting was more interested in the animal that had accompanied their ship on the way to their temporary home: the orca. Ponting was keen to capture animal behaviors with his camera, in an effort to make his own contributions to the scientific work of the expedition. The orca and the blue whales were his first opportunity, but he found them exceedingly difficult to capture on film. It was difficult to predict when they would surface, so setting up a camera to capture things like their ‘spout’ was almost impossible. But he managed to capture some of their surfacing and hunting behavior with the cinematograph.

Ponting even tried to use his equipment to document and understand whale behavior, to the extent that he could. He used the frame rate of his camera (sixteen frames a second) to measure the duration of the orca’s spout. He tried to capture their grouping and hunting patterns, but was frustrated by the challenges of catching them at the right time. He never did get a film of the blue whales spouting. He also never got a film of whales breaching, despite sitting for nine hours at a spot where he saw one of the “sportive monsters” perform the spectacular maneuver.

The intelligence of the whales impressed both Ponting and the crew, and they were amazed by the hunting ability of the orcas. Ponting himself claimed to have been hunted while trying to get just the right shot of an orca, and included a fantastical illustration of the encounter.

The illustration demonstrates some of Ponting’s editorial inclinations. Ponting was an excellent photographer but he was an equally good salesman who was constantly searching for the spectacular and the picturesque. This made him well-suited to his role on the expedition. Photographs and books were a way to make some money from exploration, and they would be in high demand back home.2 Ponting’s photographs have to be viewed with this fact in mind–he was interested in science, but the picturesque held priority.

Especially early on in the expedition, Ponting’s shots of crew members were often very carefully posed, and his shots of scientific subjects were as controlled as he could make them. His photographs of the whales are interesting in part because of the relative lack of control he had over his subjects.

Ponting found some degree of control in the ice, along with some of the most picturesque scenery he would encounter. The icebergs and ice floes of Antarctic waters captivated and frightened European explorers from the earliest days of Antarctic exploration. Edmond Halley (of comet fame) described encounters with Antarctic ice on his voyage to map magnetic variation in 1699. At first he first thought they were white mountains, and he compared them to white cliffs found in Great Britain. Later expeditions grappled with the ice, and some fell prey to it.

For mariners the ice represented unpredictability, but for the photographer they were relatively static (although still temporary) pieces of natural beauty. Ponting relished the long periods of daylight that he could use to capture the ice in different light conditions. He didn’t want to lose this opportunity, and slept very little for four days on end, working as long as “human endurance would permit.”

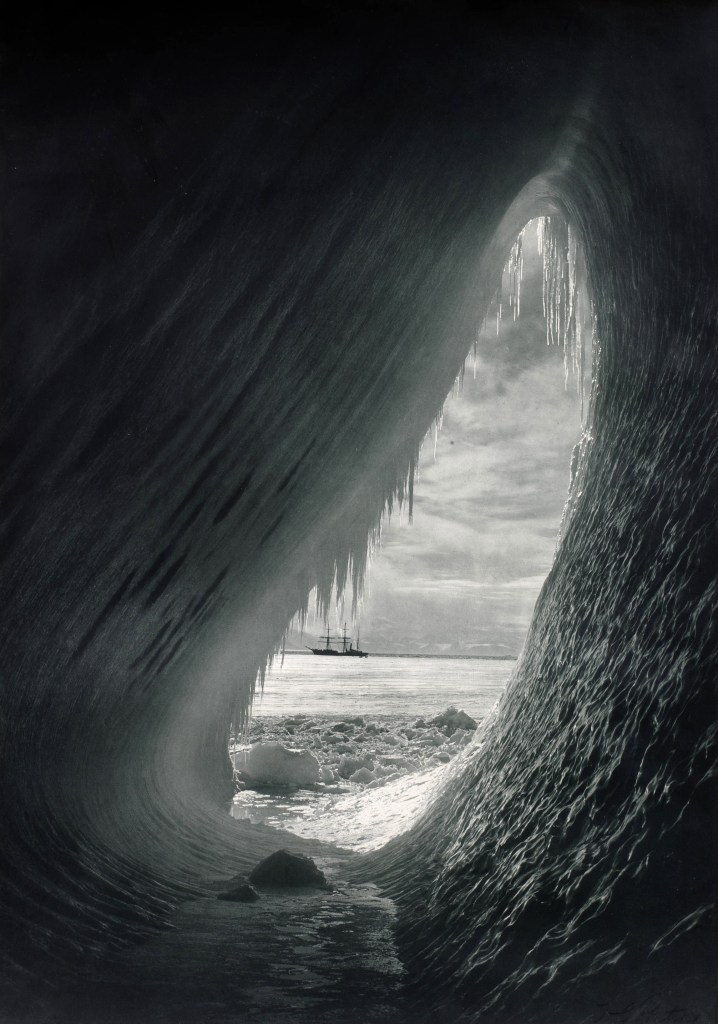

His most famous photograph captures the Terra Nova from within a grotto of ice. In his book, he described taking the picture:

A fringe of long icicles hung at the entrance of the grotto, and passing under these I was in the most wonderful place imaginable. From outside, the interior appeared quite white and colourless, but, once inside, it was a lovely symphony of blue and green. I made many photographs in this remarkable place–than which I secured none more beautiful the entire time I was in the South…I found that the colouring of the grotto changed with the position of the sun; this, sometimes green would predominate, then blue, and then again it was a delicate lilac. When the sun passed round to the west–opposite the entrance to the cavern–the beams that streamed in were reflected by myriads of crystals, which decomposed the rays into lovely prismatic hues, so that the walls appeared to be studded with gems.

Herbert Ponting, The Great White South: being an account of experiences with Captain Scott’s South pole expedition and of the nature life of the Antarctic

The elegant formations of icebergs had often been described by explorers in architectural terms, and Ponting’s photographs are some of the most successful at capturing this perspective.3 One of his most frequent subjects was the “Castle berg.”

Ponting also documented the formation of “pancake ice,” describing how small crystals coalesced into larger discs of ice. These discs grew very quickly into large sheets of ice that became ice floes. He managed to take a series of photographs showing the formation of these ice features.

The ice, the whales, seals, and penguins took up most of Ponting’s attention in the early days of the expedition. Teams of scientists had been dispatched in various directions, while Ponting stayed behind with the rest of the crew. In the next post, we will catch up with these teams, who investigated emperor penguin colonies and Antarctic geology.

Footnotes

- Quotes and information on Herbert Ponting comes primarily from his book The Great White South: being an account of experiences with Captain Scott’s South pole expedition and of the nature life of the Antarctic

- For more, see James R. Ryan, Photography and Exploration

- Kirsten Hastrup, “The Ice as Argument: Topographical Mementos in the High Arctic,” The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology, Vol 31, No 1 (2013), pp. 51-67

Pingback: History Highlights 4: Darwin’s Wild Ride, Losing Lenses, Finding Lunar Landers – Inverting Vision